Collaborative Platform Trains Students in Simulation and Modeling

NASA Technology

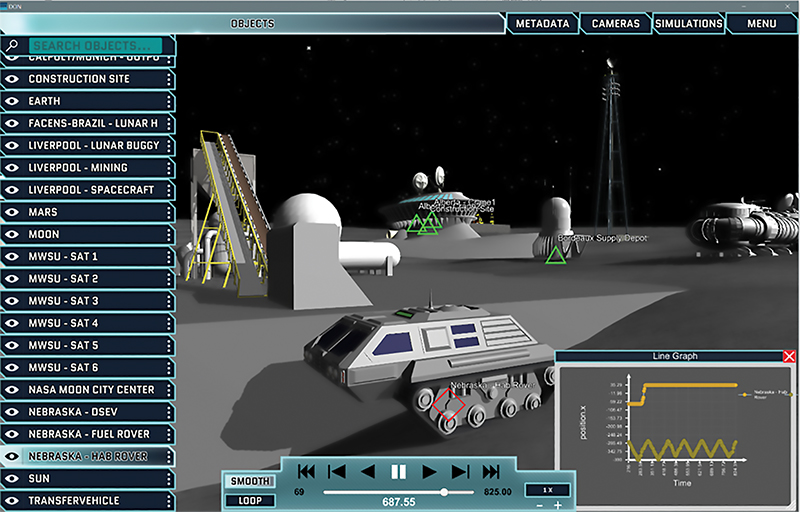

It’s the 2050s. On the far side of the Moon, in the vast, pockmarked South Pole-Aitken Basin impact crater, groups of college students from around the world are building an outpost.

In the southern sector of Moon City, a French team outfits a supply depot with smart technology. Just north of the depot is a waste management facility that a Canadian team built out of bricks made from 3D-printed Moon dust. The outpost recently began receiving tourists via the Tourism and Commercial Spaceport that Bulgarian students constructed in the Launch, Landings, and Communication area. In the Moon City Center, where most of the outpost’s 100 or so residents live and work, drones tend to crops in a greenhouse built by students from Italy.

Of course, none of this would be possible without NASA technology.

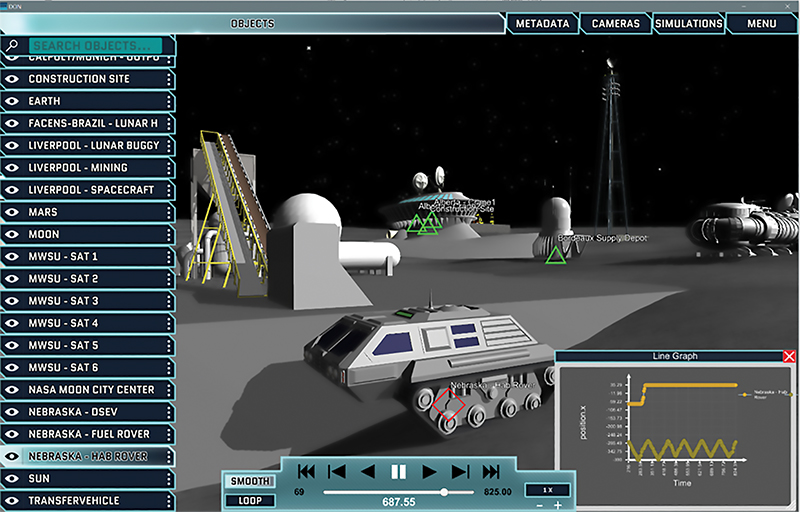

Moon City exists in a simulation and is visible through the Distributed Observer Network (DON), a simulation viewer created by NASA. The students are all in fact at their respective universities, in the present day, collaborating to build the virtual lunar city as part of the Simulation Exploration Experience (SEE). It’s a program that introduces them to collaborative modeling and simulation, a subject rarely taught in schools. Around 60-80 students participate each year.

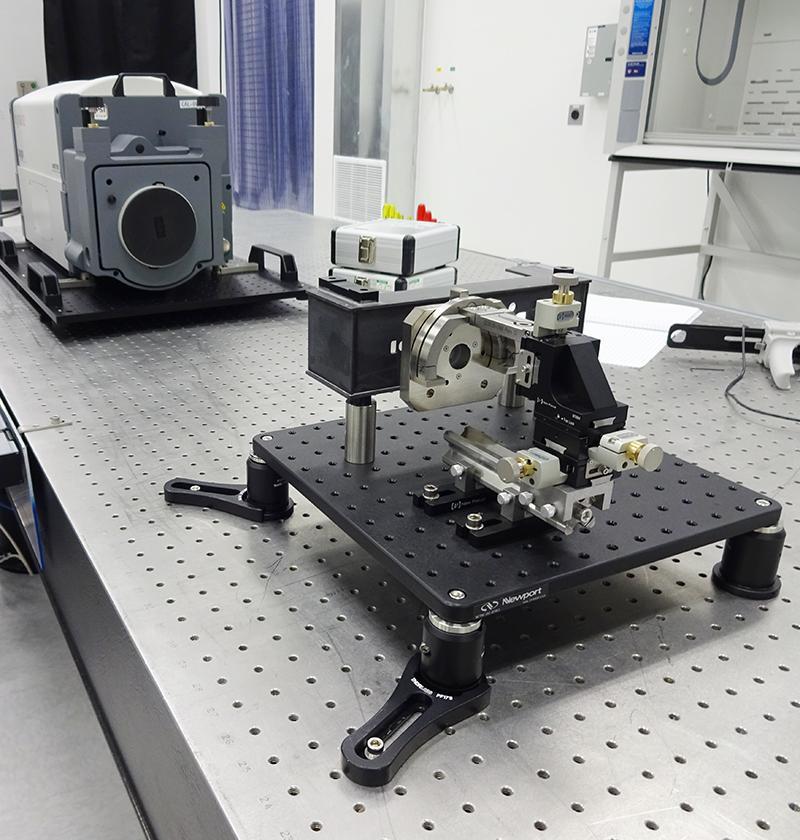

Many organizations use computer modeling and simulation nowadays, but few more than NASA. “Simulations let us learn and not make mistakes once we have multibillion-dollar pieces of equipment,” says Mike Conroy, who oversaw DON from its creation in the IT Advanced Concepts Lab at Kennedy Space Center in 2008 until his retirement at the end of 2017.

The idea from the beginning was to capture data from simulations and make them portable, to allow them to be preserved and shared. NASA teams running simulations were creating massive datasets using tools ranging from supercomputers to spreadsheets. The data was difficult to use outside the original tool, requiring the long-term preservation of the simulation system itself. DON was developed to solve this problem, allowing rich, immersive access to simulation data outside the original tools.

The viewer was built to work alongside a commercial game engine, allowing the integration of modern tools, development methods, and the latest 3D technologies. Supporting the DON visual environment is the Model Process Control (MPC) specification. MPC defines a data format that is easy for simulation tools to implement and for people to understand. Coupled with DON, MPC allows the capture of any simulation information for review, analysis, or even use by another simulation, in real time or decades later.

Conroy likens this capability to Adobe Acrobat, where data from multiple sources can be viewed and shared without the need for the original tools.

The current version of DON runs alongside the Unity 5 game engine—the same one that supports PlayStation, Xbox, iOS, Android, Windows, and most other modern platforms—but DON is versatile enough that it can and does switch game engines.

Conroy says NASA has used DON in scores of simulations across its various facilities, saving untold time and money and improving outcomes. “The more eyes on the data, the better product you’re going to get,” he says, noting that a team or engineer wanting input from another NASA group can easily share entire simulations rather than a handful of screenshots. “With DON, you can easily get a large group of people looking at the data, work around everyone’s schedule, and end up with the knowledge to make better decisions.”

The software was a runner-up for NASA Software of the Year in 2017 and is now available to the public for free download through the Agency’s software catalog, along with the accompanying MPC standard.

Technology Transfer

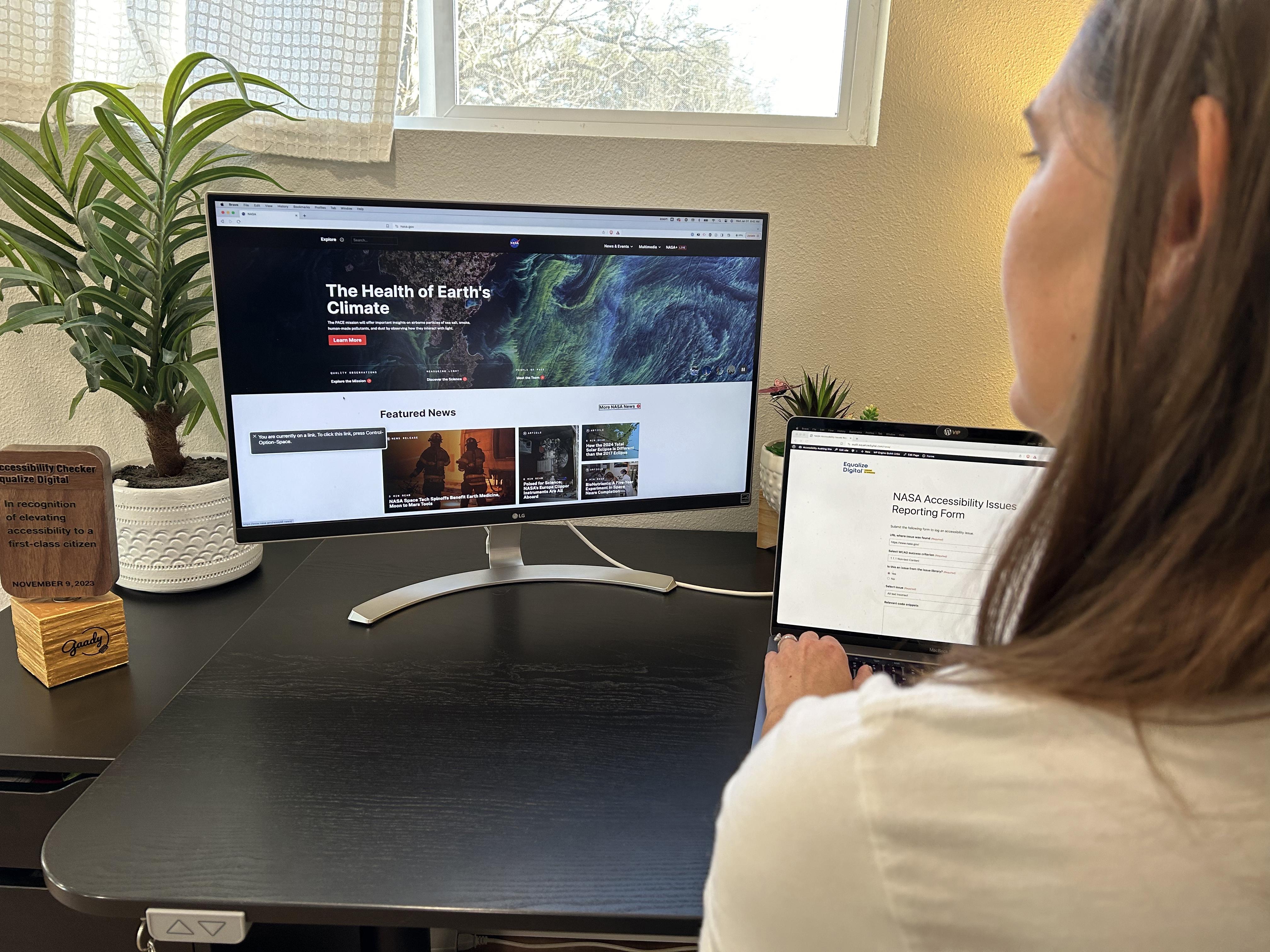

At a simulation standards workshop in 2009, Priscilla Elfrey, who works on simulation outreach at Kennedy, and Edwin “Zack” Crues of Johnson Space Center found themselves in a conversation with other simulation experts from industry and government “about how very few people applying for work in simulation knew anything about it,” she recalls.

Crues had the idea of putting college students to work on a simulated lunar mission, the inspiration that led to SEE, which he still advises. Elfrey started planning. After two years of development and with support from industry groups and several companies, students from six universities met the first challenge in 2011.

In addition to DON, NASA supplies the teams with High-Level Architecture-based software that enables the solar system model and ensures the accurate trajectories and positioning of the planetary bodies. The detailed model of the Aitken Basin that provides the challenge’s virtual setting was created at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. And various NASA personnel serve as committee members and advisors, including Conroy, who is SEE’s technical chair.

But the most support for SEE comes from the faculty at each school. “We try to make it support whatever the faculty is teaching, and they’ve been able to take what we’re doing and meld it into their own programs,” says Elfrey. “Part of the students’ assignment is that they have to come up with what they’re going to do.” Each team submits a 50-word synopsis of its project for the year. Teams then coordinate their projects, communicating not only via DON but also through video conferencing.

About 26 universities have been involved over the years, including many that have participated year after year. The University of Genoa in Italy has taken part since the beginning, while two schools in Pakistan were newcomers in 2018. Five teams went to Sofia in Bulgaria for SEE 2018 and were joined remotely by 11 more.

Benefits

There are few simulation programs or departments in American universities, especially at the undergraduate level. In 2013, Old Dominion University in Virginia graduated the first four students in the country with undergraduate degrees in modeling and simulation. “That’s when we realized we had an even bigger problem than we knew,” says Elfrey.

SEE’s overarching goal is to enhance students’ employability. Given the dearth of simulation courses and how essential the technology has become to so many workplaces, guided, hands-on experience goes a long way to that end.

“With space, we have no choice but to use simulation, but there are many professions using dynamic modeling and simulation today,” Elfrey says. She points to the widespread use of human patient simulators in medical education, the emergence of collaborative construction design software, and even the visual simulations financial companies use to display portfolios, let alone the military’s long and widespread use of simulations.

Four people who participated in the program as students are now teaching simulation in colleges and participate in SEE as faculty, says Elfrey. “We’re kind of growing our own. That was not something we had anticipated.” Another alumnus now works at NASA.

A major benefit of the software to NASA and other potential users is that it makes simulations portable not just across distances but also across time, Conroy says, noting that this is important for an entity like NASA that carries out big plans with multi-decade timelines.

Other organizations are building their own, similar software—possibly following NASA’s example. “The first time we showed DON at an international conference, we were the first to have used game engines that way,” Conroy says, noting that two years later, “almost everyone” was doing it.

But DON remains unique in its ability to manage large numbers of complex models that span distances of hundreds of millions miles.

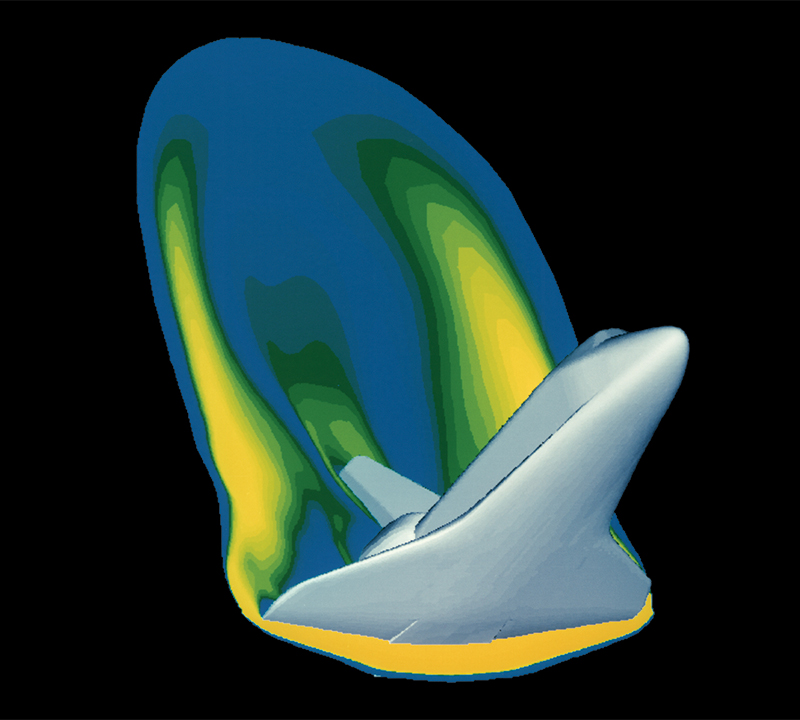

NASA uses a variety of tools to create simulations, including the computational fluid dynamics software used to simulate the aerodynamics of Space Shuttle descent here. The Distributed Observer Network (DON) can read and display any of those simulations.

A rover passes in front of part of Moon City, the simulated lunar outpost constructed by teams of students from around the world in the Simulation Exploration Experience.