From Magnetic Rocket Fuel to Semiconductors

Subheadline

A South Korean company offers ferrofluids for a variety of applications

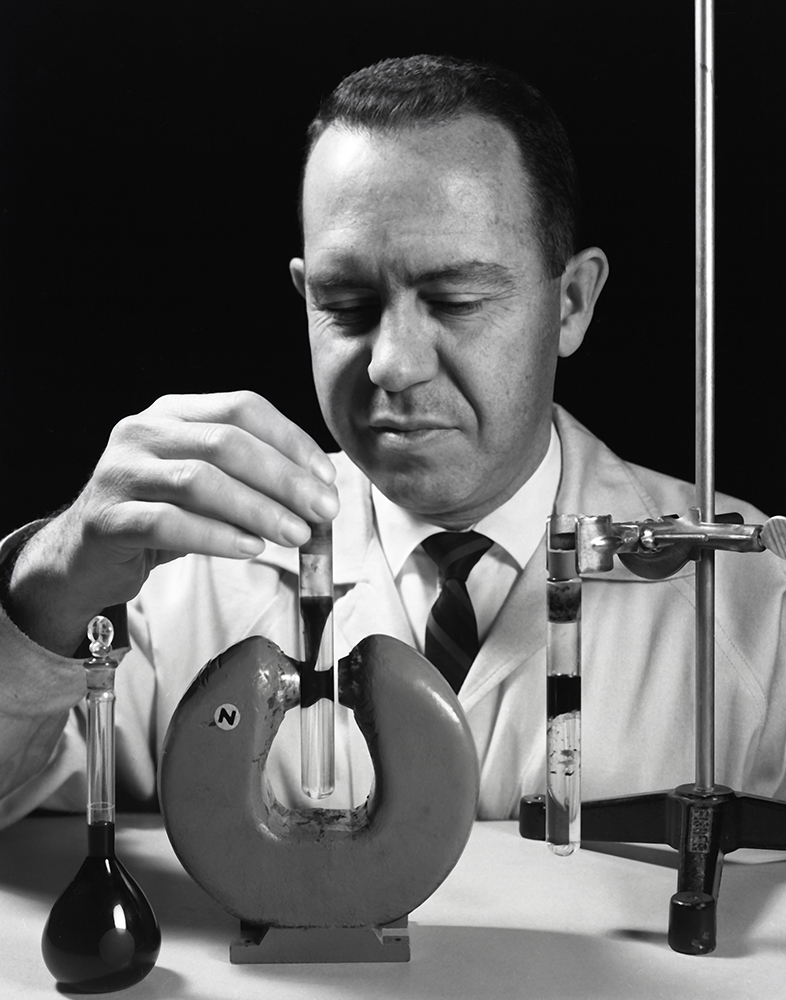

When NASA’s Stephen Papell invented the first magnetized liquid in the early 1960s, he was focused on rocket fuel – not semiconductors, speakers, luxury cars, fishing rods, or art.

Those other applications wouldn’t come until decades later, when companies like MAGRON, based in Ansan, South Korea, began offering their own line of ferrofluids – the liquid Papell first patented and for which he won multiple NASA awards.

Papell’s initial research came in the earliest days of the space program, when NASA engineers weren’t sure how liquid fuel would flow to a spacecraft engine in the absence of gravity. Papell – working in Cleveland at NASA's Lewis Research Center, now Glenn Research Center – infused fuel with tiny, coated iron oxide particles that took on magnetic properties under certain conditions, enabling an electromagnet near an engine’s turbopump to draw the fuel to it.

That idea didn’t fly (in space) because it didn’t need to – other methods of ushering fuel to the engine worked better in zero gravity. What remained, however, was the technique for magnetizing liquids – or, technically, creating superparamagnetic liquid, which takes on magnetic properties in the presence of an external magnetic field.

Further experimentation at NASA and elsewhere in the years that followed revealed additional processes for making ferrofluids out of various materials, and a variety of new applications.

MAGRON’s trade manager Kwon Se-heon said he knew NASA had developed the first ferrofluid decades ago. In designing their own products, the company’s developers referred to Korean papers and academic journals with more recent research and findings.

The company's most popular product is a ferrofluid for sealing out gas and dust that is used in the manufacturing of semiconductors, Kwon said. Semiconductors are typically used in electronics and solar cells.

Ferrofluids can create an airtight seal by sticking magnetically to the edges of a gap between moving parts. They are extremely slow to evaporate or degrade and highly resistant to extreme heat and chemicals, so they are long-lasting, even under harsh conditions.

MAGRON also sells ferrofluids for waterproof fishing reels and for art and educational purposes.

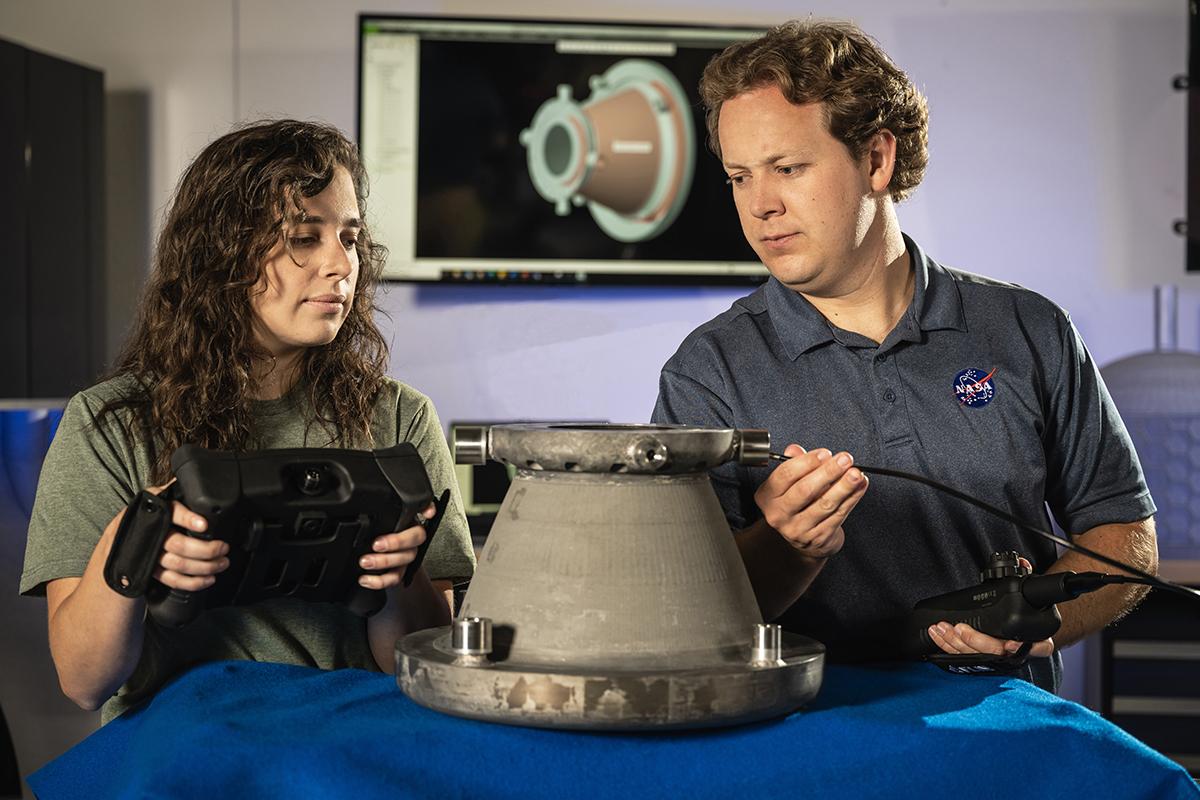

Ferrofluids could still one day be useful in space, according to Narayanan Ramachandran, who works on propulsion fluids at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, and has published research on ferrofluids.

“The sealing properties of ferrofluids – they seal against dust as well as differential pressure – could be used, for instance, in an astronaut visor or in rotating system seals, such as on a rover or even a lab circling the Moon,” Ramachandran said.

Back on Earth, researchers are also studying ferrofluids in cancer therapies, developing approaches that could one day change how doctors treat cancer patients.

Ferrofluids were first developed at NASA in the 1960s by Stephen Papell, pictured here, at Lewis Research Center, now Glenn Research Center in Cleveland. Credit: NASA

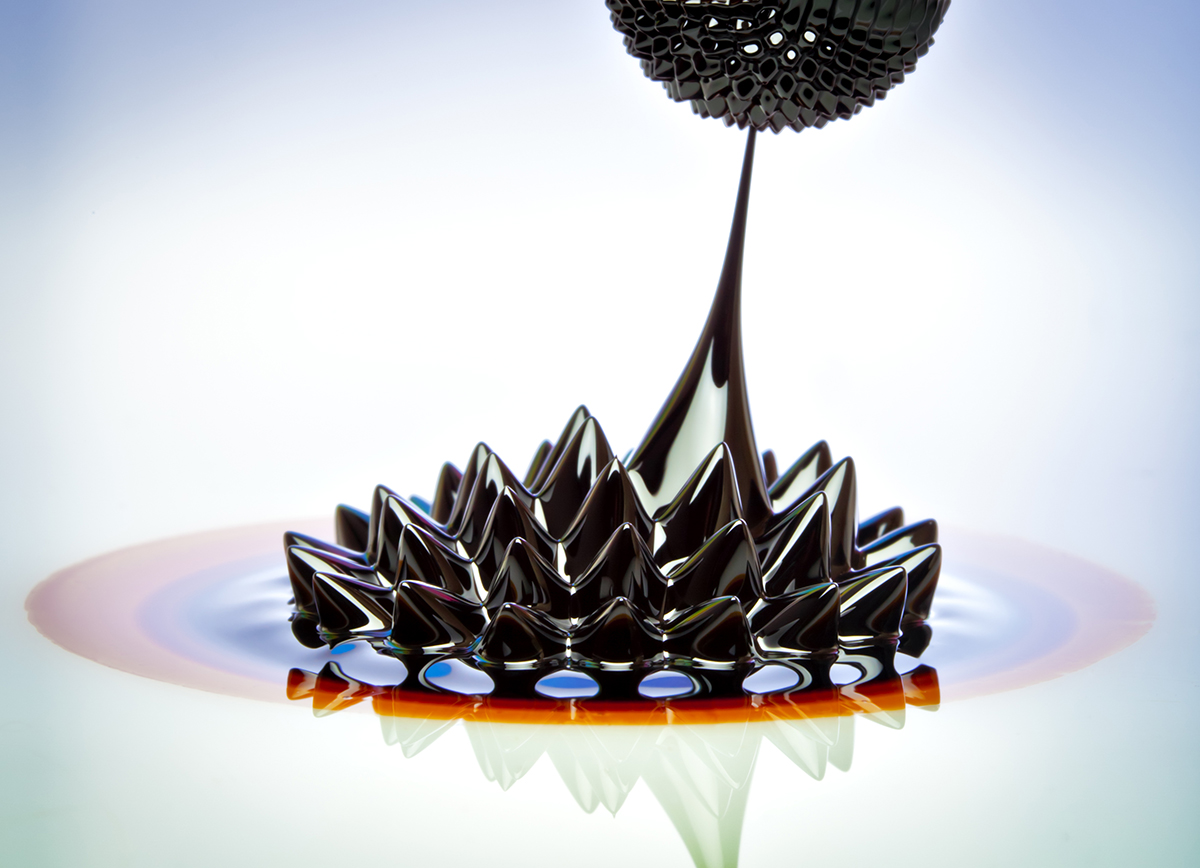

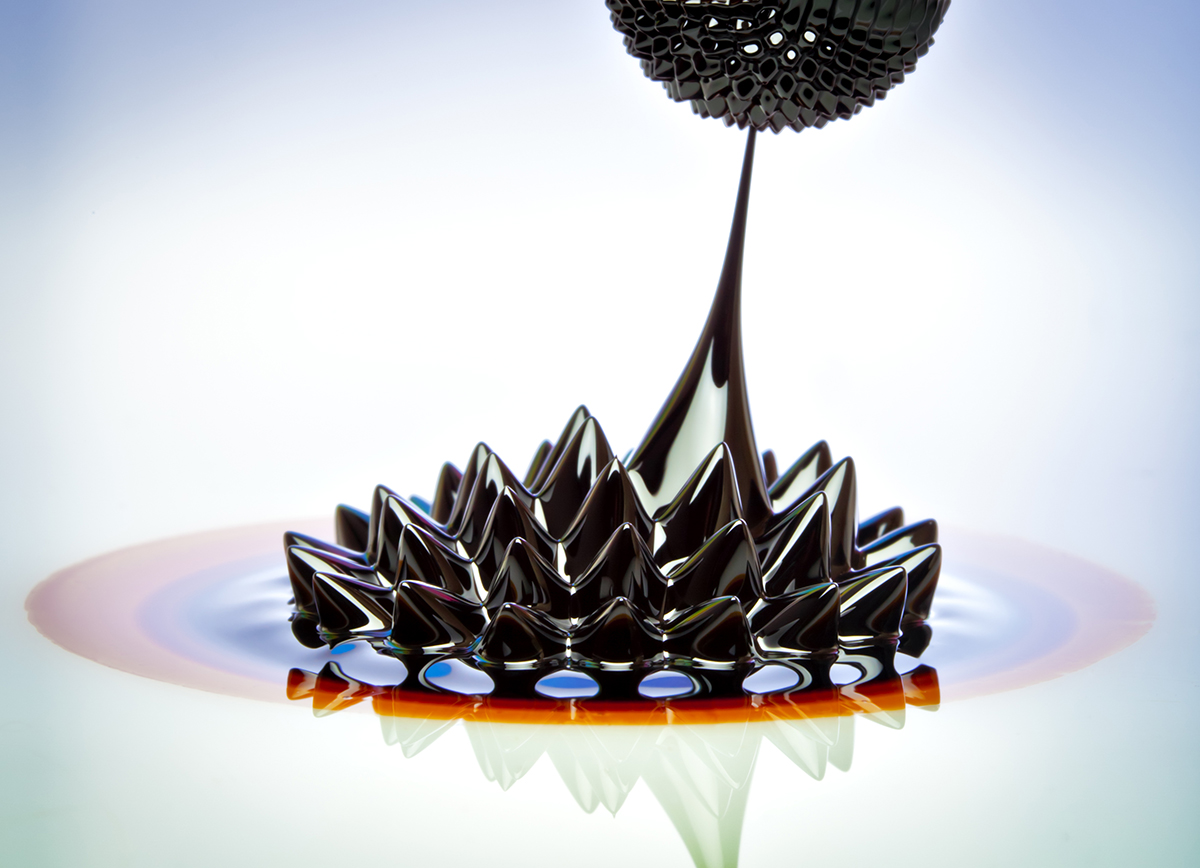

Ferrofluids – liquids infused with magnetic properties that activate under certain conditions – are sold by the South Korean company MAGRON for use in semiconductor manufacturing, fishing rods, and other consumer products. Credit: Getty Images