NASA Data Helps Beavers Build Back Streams

Subheadline

Nature's engineers, beavers, get help from NASA to mitigate drought, wildfire

When beavers move into a stream to start a homestead, they also improve their ecological neighborhood. By engineering their ideal environment — a marshy, plant-rich area — they provide homes, food, and refuge for countless other animals.

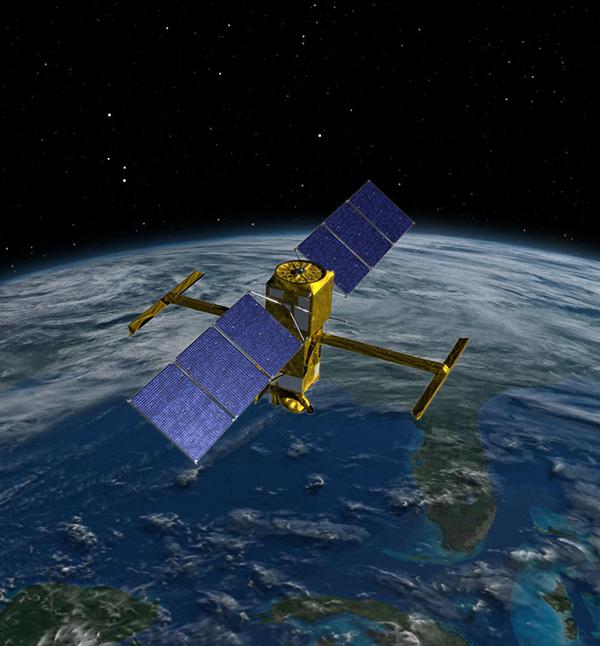

Beaver dams slow down streams to create ponds, thereby preventing erosion, providing plant and wildlife habitats, and protecting vital watersheds. The wetlands they create can slow the progress of wildfires and offset the effects of drought. This has made returning beavers to the arid western United States a decades-long effort. And now Earth-observation data, much of it from satellites whose construction was managed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, is helping.

Boise State University received a space agency grant to develop a suite of monitoring tools to help plan restoration projects and track changes in river systems. Utah State University was included in the funding, and both schools use data from NASA-built satellites to support the return of beaver populations for stream restoration. Observations from low-Earth orbit play a key role in all of this work, from choosing sites with the best likelihood of successful restoration to monitoring the subsequent impacts of these efforts.

When NASA’s Research Opportunities in Space and Earth Science (ROSES) program sought projects that could benefit from remote sensing data, Boise State proposed its Mesic Resource Restoration Monitoring Aid (MRRMaid) program. Mesic environments are those with moderate amounts of water throughout the growing season. The open-source MRRMaid program uses data from the Landsat satellites, as well as other satellites, to observe the abundance of streamside vegetation over time, a measure of a mesic environment’s health.

Not many ROSES proposals have commercial outcomes, said Cindy Schmidt, associate manager for NASA’s Ecological Conservation program. She welcomed the opportunity to see benefits for farmers, ranchers, and others who rely on local water to support their livelihood.

“Idaho Fish and Wildlife and other organizations are extremely interested in bringing beavers back, but they have challenges working with landowners and ranchers. There’s a perception that beavers destroy things,” said Schmidt.

Leveling the Pond

After beavers were nearly eradicated by hunters and trappers in many Western states, runoff from mountains and human development could run through streambeds unimpeded. With no barriers to slow the flow, wetlands drained, and streambeds became straighter and deeper, causing the water table to drop and leaving some streams dry for long periods each year.

To support ecosystem restoration, the online Beaver Restoration Assessment Tool (BRAT), created by Utah State and supported in part by the NASA ROSES grant, identifies ideal restoration sites to attract beavers. Sarah Koenigsberg, a graduate student at Utah State studying riverscape restoration, has been working with the BRAT team.

One factor that can raise opposition to employing beavers in stream restoration is concern about the damage they might cause, but Koenigsberg said there are simple ways humans can support a harmonious coexistence.

For example, if a beaver dam is close to human infrastructure, a pond leveler can set the maximum water level. Then beavers have the water necessary for protection and their underwater lodge entrance, while excess water escapes downstream. “You’re basically outsmarting the beavers by using a pipe to make a hidden leak in the dam,” said Koenigsberg, noting that beavers can benefit the environment without harm to homes or businesses.

“We have to pay attention to human concerns as well as ecological ones for long-term success, and that’s one of the things I love about BRAT,” she added.

BRAT uses satellite data to analyze stream conditions and rank areas that are likely to benefit the most from beaver-assisted restoration while encountering the least conflict. The tool considers factors such as vegetation for food, available trees for dam building, water flow, and existing human infrastructure. Watershed managers, nonprofits, and others work with Utah State to assess proposed locations. Once a site is chosen, attracting beavers might be as simple as constructing a temporary beaver-dam analog or a post-assisted log structure. These begin to make degraded areas hospitable to beavers.

Buck-Toothed Ecosystem Engineers

“Idaho was one of the first places thinking about re-wilding with beavers. Way back in the ’30s and ’40s, ranchers were already trying to get beavers on their lands,” said Jodi Brandt, associate professor in Human-Environment Systems at Boise State. Funding is available to implement restoration, said Brandt, but frequently there is not money available to monitor the results. Satellite data offers a solution.

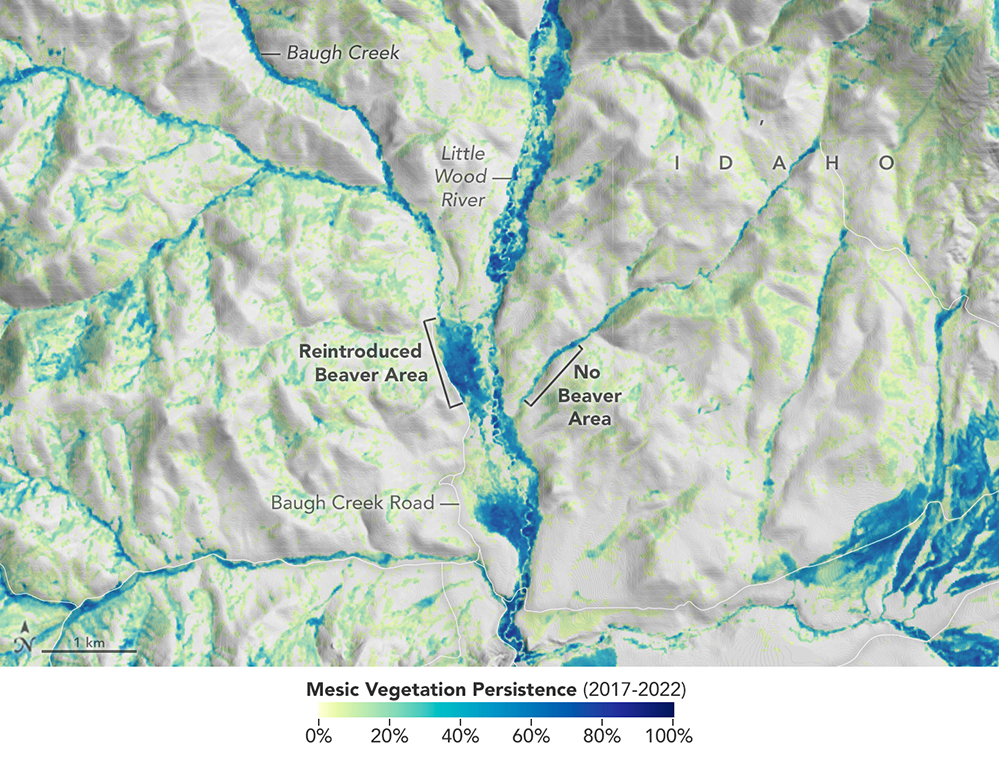

“The MRRMaid approach to monitoring uses satellites that are repeatedly passing overhead, so we can map changes from above,” explained Brandt. Data from Landsat satellites along with the ESA’s (European Space Agency) Sentinel missions can be analyzed to measure changes in water and vegetation over time. One rancher who attracted beavers back to his land hopes drawing attention to his success will demonstrate the benefits of stream restoration. With satellite data, “we can provide empirical evidence of what’s happening on his land,” said Brandt.

Businesses and organizations need proof of conservation success to secure funding or build support for projects. Among MRRMaid’s users are state and federal agencies, conservation groups including the Nature Conservancy, land trusts, and watershed managers.

In addition to creating habitats for fish and other wildlife, and thereby supporting recreational activities and offering natural beauty, wetlands serve as an animal refuge during wildfires. Beavers build canals into neighboring woodlands, spreading water and nutrients, making vegetation fire-resistant, and creating places that can shelter wildlife in the event of a fire. Those ponds also filter toxins and pollutants from the water before and after a wildfire, making the area healthier and more resilient.

Filling Data Gaps

The current versions of MRRMaid and BRAT require users to understand GIS — geographic information systems — to run simulations and generate reports. Because most people don’t have that knowledge, the Boise State and Utah State faculty and students run query requests from the public as resources permit. Work is underway to make the tools easy for anyone to use.

Even with access to the best remote sensing and data, though, there’s value to seeing change on the ground from a human vantage point, and that’s where Phlux comes in. This new smartphone photo app makes it easy to set a photo point and allow anyone to upload their photos from that exact spot again and again, creating a series of images of a restoration site that shows change over time.

Brandt said public engagement is critical for success. “We have worked with ranchers in Idaho who are doing a lot of stream restoration. They are often excellent stewards of the land,” said Brandt. Those success stories, together with data from BRAT and MRRMaid, help build public support for conservation efforts, she said.

Federal agencies like the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management, which manage more than half of Western land, are engaged in multiple restoration projects. GIS allows them to use BRAT and MRRMaid to maximize those efforts. Once the updated programs are available, anyone in Idaho, Utah, Oregon, and other Western states will be able to identify the best stream restoration sites.

“That’s what applied science is all about — getting the users whatever is needed for environmental decision making,” said Schmidt of NASA Ecological Conservation. “We can’t do it without private companies. The future of our planet relies on these commercial partners working with us to do things more sustainably.”

And sometimes those commercial partners need a little help from animal allies.

A 3-month-old beaver kit enjoys its new home after its family was relocated from a concrete drainage ditch in urban Aurora, Colorado, to a private ranch in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. Credit: Sarah Koenigsberg

Landsat data helps Utah State University identify streams where beavers can be reintroduced to help improve an ecosystem. Boise State University also uses Landsat data to show just how much beavers help.

The vegetation in this satellite image indicates where streams or creeks are flowing and reveals the benefits

of beaver activity. Credit: NASA

Beaver dams and canals create wetlands and retain water, providing a wildfire-resistant safe haven for wildlife and speeding post-fire recovery, as this region in Baugh Creek, Idaho, shows. Credit: Schmiebel, CC BY-SA 4.0

This beaver dam analog was built by crews from Anabranch Solutions in the summer of 2023, as part of their effort to restore stream processes and prepare the watershed for beaver reintroduction. Such human-made dams can entice beavers to areas that will benefit from their work. Credit: Sarah Koenigsberg

This is one of the primary dams on the downstream edge of an expansive beaver complex that survived the catastrophic Bootleg Fire of 2021 in Klamath Basin, Oregon. Beaver ponds create wet areas with fire-resistant vegetation that can hold off wildfires and provide refuge for fleeing wildlife. Credit: Sarah Koenigsberg

A beaver family nibbles on aspen branches just up Logan Canyon from Utah State University, in Spawn Creek, Utah. Credit: Sarah Koenigsberg