Clean Air Tech for Spacecraft Helps Fight Pandemic

Subheadline

Clean air, always a priority in space, gained importance on Earth in slowing virus spread

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, as it became clear that the novel coronavirus was transmitted through the air, several companies realized their NASA-derived air-quality technologies could help combat its spread. And they soon found themselves overwhelmed by demand from schools to hospitals, shopping centers, office buildings, airports, and even buses.

One of these was ActivePure Technology, formerly Aerus Holdings. Just after lockdowns took effect in March of 2020, Joe Urso, CEO and chairman of the Dallas-based company, said ActivePure had gone through six months’ worth of its inventory in the preceding few weeks.

By that December, Urso said business was steady at about five times pre-pandemic levels.

At TFI Environmental Company Inc., CEO and director John Hurley noted that products like his company’s Respicaire air purifiers, which use the same family of technology as ActivePure’s, usually fill a small niche – “until something like this happens.”

Accustomed to working to convince people of the importance of indoor air quality, in late 2020 he said his Toronto-based company, swamped with orders, no longer had to convince anyone.

And by March of 2021, Italian company Airgloss had been out of inventory for months. Airgloss makes air-quality sensors, not purifiers, intended to help HVAC systems and air purifiers improve efficiency and air quality. It soon became apparent, though, that the company's technology could help reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission.

Airgloss cofounder and CEO Ciro Formisano echoed Hurley’s assessment: “Before COVID-19, air quality was something you had to think about, but it was not that interesting to many people. Now people are becoming more and more interested in what’s in the air.”

Spacecraft: The Ultimate Indoor Environment

Respicaire’s most popular products, and all of ActivePure’s air purifiers, are based on a technology developed in the 1990s at the Wisconsin Center for Space Automation and Robotics (WCSAR), a NASA Research Partnership Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison at the time, sponsored by the space agency’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Researchers there wanted to eliminate the plant hormone ethylene from the air around plants in spacecraft. Without gravity to move the air around, ethylene accumulated around plants, causing premature withering. But the solution they devised, known as photocatalytic oxidation, eliminated a lot more than ethylene.

Photocatalytic oxidation starts when ultraviolet light hits titanium dioxide, a common, naturally occurring chemical compound installed inside the device. This releases electrons, which then combine with oxygen and water molecules in the surrounding air. The oxygen and water, now with a charge, attract organic contaminants, causing reactions that turn them into carbon dioxide and water. Among the pollutants destroyed are volatile organic compounds and other harmful or odor-causing chemicals, as well as mold spores, bacteria, and viruses.

Marc Anderson, the professor who led the project at WCSAR, was one of two researchers leading efforts during the 1980s to purify air and water with titanium dioxide-induced photocatalytic oxidation – the other was Akira Fujishima at the University of Tokyo. While the technology has gained popularity in the last 20 years, Anderson said, “Fujishima and I were among the earlier scientists refining this photocatalytic process to make it a practical environmental technology. Now they’re pretty much all building on work we all did nearly three decades ago.”

At TFI Environmental, Hurley said he was surprised when he discovered the technique while scouring air-purification research. “NASA, to me, was rocket engines and fancy technology and all kinds of expensive gear.”

However, photocatalytic oxidation wasn’t the perfect solution. For example, the process can generate ozone, which can be harmful, and organic compounds might be only partially broken down, resulting in unwanted chemicals. Each company has made advances to mitigate these downsides.

Testing has shown that neither company’s devices add ozone to the air. Last summer, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cleared ActivePure’s new Medical Guardian product as a medical device on the basis of its efficacy and safety, including assurance that it doesn’t cause concerning chemical by-products through partial oxidation. Respicaire devices often incorporate a combination of photocatalytic oxidation and other technology like activated-carbon filters that remove chemicals and particulate matter.

Marshall scientist Jay Perry, who has worked with photocatalytic oxidation as the center’s senior engineer for life-support systems and space station air quality, emphasized that such combinations of technology are advisable. “Photocatalytic oxidation and ionizing technologies are not standalone indoor air-quality solutions and must be part of a well-designed and -maintained HVAC system that includes highly effective filters to achieve good indoor air quality,” Perry said.

Testing last year showed that both companies’ purifiers were effective in eliminating the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Respicaire’s products, including the popular OXY 4 air purifiers, are all designed to fit into the ducts of heating and cooling systems, where multiple units can be stacked to purify the air in larger commercial spaces, Hurley said.

ActivePure now incorporates photocatalytic oxidation into about 100 different air purifiers under several brand names, from portable units to those that fit in air ducts, cars, or elevators.

‘Electronic Nose’ Smells Trouble

Airgloss CEO Formisano originally helped create his company’s technology, an “electronic nose,” working with a university in Rome, but the technology got a boost when the Italian Space Agency selected it for testing, with NASA’s help, on a U.S. module of the International Space Station.

It uses a series of oscillating quartz microbalances – scales that sense tiny weight variations – coated with different polymer films and coupled with artificial intelligence software. The polymers react to different substances in the air, causing slight changes in the microbalances’ oscillation frequencies. Together, these changes in frequency let the pattern-recognition software identify and quantify substances in the air.

“It fell within the general interest of NASA for technology to detect contaminants aboard the space station,” said Francesco Santoro of Italy’s Aerospace Logistics Technology Engineering Company (ALTEC), a public-private company co-owned by the country’s space agency. Santoro, then the ALTEC team leader for the Italian Space Agency office at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, helped prepare the experiment to fly to the station in 2011.

NASA helped sponsor the experiment, known as the Italian Electronic Nose for Space Exploration, which flew on space shuttle mission STS-134.

Formisano said developing a product for space taught the company how to build and rigorously test robust sensors. “Without NASA, Airgloss wouldn’t exist.”

The testing showed promise, and in 2014, Formisano and colleague Maryna Lotsman founded Rome-based Airgloss to commercialize the technology. The company’s first standalone product, ProSense, designed for commercial, public, or office space, was released in 2018, followed by the more home-oriented Comfort Kit in 2021.

The devices monitor volatile organic compounds and dangerous gases as well as humidity and even ambient noise and lighting. Working together with a thermostat, and possibly an air purifier, they automate a building’s entire air-management system. They also use WiFi to alert users to issues with the indoor environment and deliver regular reports and tips to improve it.

Airgloss is also working with original equipment manufacturers to integrate its sensors into appliances, such as a range hood that starts up automatically when it senses cooking odors, and even automobile ventilation systems. And in light of the pandemic, the company started working with manufacturers to automate air purifiers.

Sniffing Out Virus Risks

In one pilot program, the company partnered with energy-efficiency-as-a-service company Minimise to automate climate control efficiently in a Florida school district. The program happened to coincide with school reopening plans, and organizers realized Airgloss technology could sense room occupancy by detecting levels of carbon dioxide and other human by-products. As a room becomes more crowded, the HVAC system can inject more fresh air, diluting expelled breath, and it can turn on air purifiers or suggest other actions.

This led to a display panel that other customers now use to show the “virus propagation risk index” in shared spaces, Formisano said. The information lets people know to reduce crowding or take other steps. “People are becoming aware that they have to contribute to COVID-19 mitigation.”

These and other projects ensure that interest in Airgloss technology will continue after concerns about the novel coronavirus subside.

A fume extraction company is experimenting with the sensors for detecting residual pollutants in workplaces. Other pilot projects successfully tried out the technology to determine the purity and quality of petroleum, to let drones analyze pesticides on crops, and to detect food deterioration inside refrigerators. A partnership with the European Institute of Oncology in Milan determined that the sensors had a more than 85% success rate in detecting early-stage lung cancer, although Formisano said the company has yet to begin the lengthy certification process for medical applications.

Meanwhile, he said, customers are looking for help from products they trust. “And people trust us because our technology has been proven through space station testing.”

Santoro agreed: “This is a shining example of how space-tested technology can have follow-on applications on Earth.”

NASA astronaut Peggy Whitson checks out soybean plants growing in the Advanced Astroculture (ADVASC) plant growth chamber on the space station in 2002. The photocatalytic air scrubber that regulated ethylene levels in ADVASC and its predecessor turned out to eliminate many other contaminants and eventually led to several lines of commercial air purifiers. Credit: NASA

As engineers at the NASA-funded Wisconsin Center for Space Automation and Robotics built the Astroculture plant growth chamber in the 1990s, they came up with photocatalytic oxidation as a way to prevent the buildup of ethylene, a plant growth hormone that accelerates ripening and withering. Credit: NASA

ActivePure Technology’s Medical Guardian air purifier got Food and Drug Administration clearance as a medical device in June of 2020, as hospitals and other medical facilities were looking for ways to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus. Credit: ActivePure Technology

The OXY 4 air purifier, based on photocatalytic oxidation, is one of the most popular Respicaire air purifiers. This one incorporates two modules to scale up for a large commercial space. Credit: TFI Environmental Company

Two OXY 4-MB air purifiers from Respicaire are installed in the air handling unit at Synergy Flavors Inc. in Wauconda, Illinois. Credit: Jensen’s Plumbing & Heating

Italian astronaut Roberto Vittori holds up the Italian Electronic Nose for Space Exploration (IENOS) experiment aboard the space station, where he tested the technology in 2011 with help from NASA. Credit: NASA

Three of the IENOS devices were delivered in a single package to the space station in 2011. The IENOS inventors have now commercialized the technology through the Italian company Airgloss. Credit: NASA

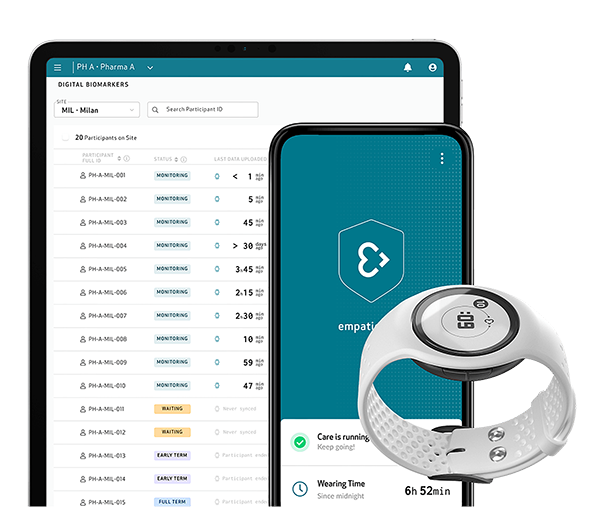

Airgloss’ air quality sensors work in conjunction with a thermostat to regulate ventilation and manage indoor air, sending alerts and reports. During the pandemic, the company learned how the sensors could calculate a space’s risk of COVID-19 spread. Credit: Airgloss

Airgloss sensors measure volatile organic compounds, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, methane, humidity, and even ambient noise and lighting to generate detailed reports that they deliver to devices via WiFi. Credit: Airgloss