Space-Grade Insulation Keeps Beer Colder on Earth

NASA Technology

A class of insulation invented to help NASA with a range of daunting tasks, from storing liquid hydrogen or helium to insulating spacecraft and keeping astronauts comfortable in their spacesuits, is now keeping beer kegs cold at parties and barbecues around Philadelphia and beyond.

Most everyday insulation, such as traditional clothing, blankets, or rolls of fiberglass, is designed primarily to prevent the conduction of heat from one side to the other. Cloth and fiberglass are poor heat conductors, as are the pockets of air they trap. But NASA engineers calculated early in the Space Program that to insulate a spacesuit against the temperature extremes of space, conventional insulation would have to be several feet thick. They had to find another way.

By the time the Space Program got underway, engineers were already working with insulation that reflected radiated heat, rather than simply damping conduction. Reflective surfaces had been added to some building insulation and were used in Thermos bottles, for example. But NASA mastered reflective insulation, turning it into a versatile and extremely effective technology now known as radiant barrier.

A key innovation was layering lightweight, reflective materials to increase their insulating power. The first such multilayer reflective insulations were created under contract to Marshall Space Flight Center in the mid-1960s, when the Linde Division of Union Carbide Corporation delivered a series of insulations made with layers of thin aluminum foils and sheets of fiberglass, and the Metallized Products Division of National Research Corporation created an insulation made from sheets of crinkled, aluminized Mylar. The latter, known as NRC-2, became the model for a host of “superinsulation” materials that would find a multitude of uses in space and on Earth.

Mylar is a trade name for a remarkably thin, lightweight, and durable polyester film developed by DuPont in the mid-1950s. A line of similar materials followed. The first metallized polyester thin film was created in the late 1950s by depositing vaporized aluminum onto Mylar in a vacuum. One of its earliest uses was in NASA’s Echo 1 satellite balloon, an early communications satellite that used the material’s reflectiveness to bounce radio and radar signals back to Earth.

Metallized Mylar turned out to reflect heat just as well as it did radio transmissions, and NASA researchers found that when sheets were layered half an inch thick without touching each other, it created an insulation vastly more effective per pound than any other in the vacuum of space.

As the Space Agency began adapting this new class of insulation to various uses, NASA and its contractors made advances on virtually all fronts, including tensile strength, fabrication and application techniques, testing procedures, predictive modeling of performance, and fine-tuning of materials and configurations. Building on NASA’s work, manufacturers began experimenting with different metals on a variety of polymer thin films.

The resulting materials came to be used not just in all spacecraft and spacesuits but in commercial spinoffs that include clothing, firefighting and camping gear, building insulation, cryogenic storage, magnetic resonance imaging machines, particle colliders, and commercial satellites, to name a few. Nearly half the issues of Spinoff since 1976 have featured products incorporating radiant barrier technology.

Technology Transfer

In June of 2015, the evening before the annual Philadelphia International Cycling Classic, Dan Gwiazdowski and friends were preparing for a backyard get-together at aalong the race route. They had already picked up a beer keg and were contemplating how to keep it cold overnight. Relying on ice alone would require the inconvenience of periodically refilling the tub of ice throughout the night.

“I was thinking, the keg is already cold, we just need to keep it from getting hot,” Gwiazdowski recalls. “I was like, ‘Aha!’ I remembered having an emergency blanket in my car.”

He wrapped the reflective Mylar blanket around the keg and ice bucket the best he could, and he and his friends were still drinking cold beer when the race ended the next day. “We realized we were onto something,” he says.

Gwiazdowski had founded the design company JUNTO LLC in 2011, naming it after a group founded in his city by Benjamin Franklin, which met to drink and discuss politics, morals, and philosophy. Franklin’s Junto is credited with the colonies’ first lending library and the city’s first fire department. “It was a creative collaborative that benefited the community around it,” Gwiazdowski says.

Likewise, he says, he tries to involve others in collaborative thinking to “create simple products that consider environmental impact, are beneficial to users, and apply creativity to result in smart design”—sometimes around a keg of Philadelphia microbrew.

In that vein, following his improvised keg-cooling experiment, he started researching reflective insulation and testing prototype keg covers. While some materials were too thick and heavy for his liking, others were too flimsy to stand up to reuse. Then he came across a product line called HeatSheets (Spinoff 2006), manufactured by Advanced Flexible Materials Inc. (AFMInc).

That company was founded by David Deigan, a former employee of the National Metallizing Division of Standard Packaging Corporation, an early NASA supplier of reflective insulation. Before shutting down, National Metallizing had started spinning off commercial products, and Deigan founded AFMInc to continue doing so, manufacturing blankets, ponchos, and capes for emergencies, outdoor adventures, and, most famously, marathons and other athletic events.

Gwiazdowski contacted the company, got a sample, and did some testing. “It was lightweight, very strong, flexible, recyclable, and very effective,” he says.

Based on the material, he came up with the design for his KegSheet product, which AFMInc agreed to manufacture for him.

In early 2016, the Space Foundation announced that the KegSheet had been officially space certified.

Benefits

When wrapped over a keg and ice bucket, a KegSheet keeps beer cold “pretty much all day,” Gwiazdowski says, noting that he wrapped the keg for the 2016 bike race at about 5:00 the night before the event. “By five in the afternoon the next day, we still had beer that was drinkably cold.”

In a test on a sunny, 90 °F day, he found that the beer actually got cooler over the first several hours. After five hours, a wrapped keg was almost 4 degrees cooler than its initial temperature, while an unwrapped control keg in ice had risen

17 degrees in temperature. At the end of eight hours, the unwrapped keg was more than

24 degrees hotter than its starting temperature, while the KegSheet-insulated one was just

9 degrees warmer.

Another option, he points out, is to wrap a keg without ice to avoid the mess and hassle. In a separate test on a cooler day, Gwiazdowski found an unwrapped keg on ice warmed 10 degrees after eight hours; an insulated keg without ice was just 7 degrees warmer.

He notes that the insulators are lightweight and easily portable, fitting in a pants pocket when folded. They’re also strong and washable, allowing repeated reuse. And they can be recycled with plastic shopping bags.

Gwiazdowski has been working to make the insulators available where kegs are rented. “Recently, we’ve been making a concerted effort to get out to retailers and beer festivals,” he says. KegSheets began showing up at retailers, mostly around Philadelphia, in late summer of 2016, going for anywhere from $8 to $15.

He notes that they quickly pay for themselves through money saved on ice.

“It’s incredible to be able to leverage a technology NASA’s created and apply it to something that’s fun and exciting—in this case, drinking beer.”

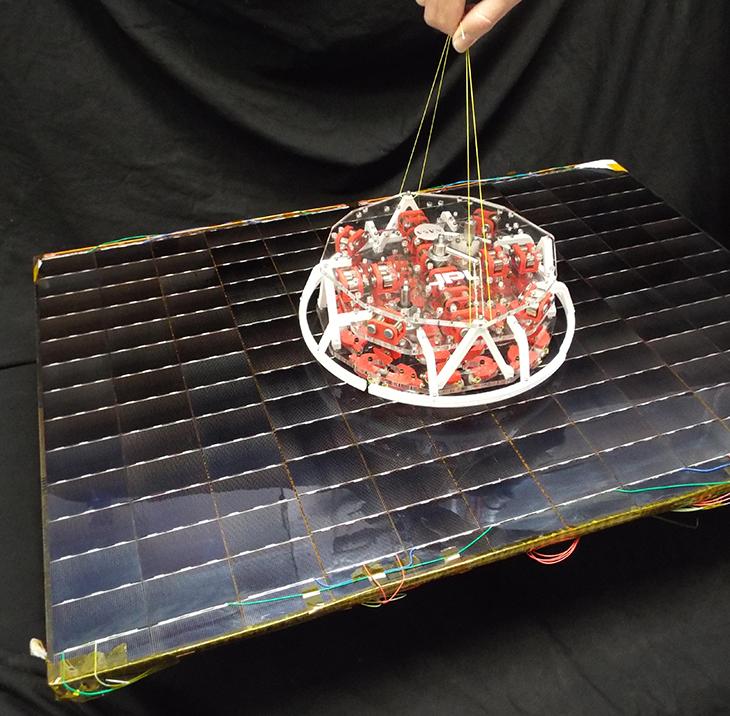

KegSheet beer keg insulators made with multilayer reflective thin-film insulation pioneered by NASA, are not just effective but also lightweight and low-mass, folding up small enough to fit in a back pocket.

In Goddard Space Flight Center’s Space Environment Simulator, an engineer lays radiant barrier insulation over wires on the floor, keeping the heat they generate from contaminating the chamber, which is used to mimic the environmental conditions of space. Image courtesy of Chris Gunn, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0